Presentation Matters: Pitchdeck UI

Sunday, September 26, 2010 at 10:33PM

Sunday, September 26, 2010 at 10:33PM

There are varying schools of thought as to what deliverables are required to attract the interest of an investor. Among them, the three most important ingredients are: the product demo, the financial model, and the pitch deck.

At the earliest stages of investing, many view the demo as a key reflection of a team's ability to articulate their vision. Jason Calacanis famously said that he does not even look at business plans. In the growth or later stages of funding, a company's financial performance is viewed as a leading indicator of both the attractiveness of the underlying market opportunity and the ability of the team in question to execute on that basis. Product is taken as a given here, and so demos lose relevance.

Having spent time investing at each stage of the venture lifecycle, I am a big believer that a company's pitch deck is the most important means of securing capital (either in working capital for expansion or liquidity for founders or early shareholders). And while I am absolutely blown away by the quality of the entrepreneurs that I meet with and the products that they build, I continue to be underwhelmed by the quality of the materials used to present their vision.

Pitch decks are sales documents. Think of them as a kin to the resume. Anyone that has ever hired anyone (or for that matter interviewed for a job) knows that a CV is tool used to tell a story. When that tool is not sharp (irrelevant content, poor formatting, lack of attention to the specifications of the job), the tool itself can get in the way of accomplishing the task for which it is used, and job applications wind up in the waste bin before even getting a substantive chance. A company's (and more specifically a CEO's) ability to sell is one of the most important proxies for its success. Sales are crucial to hiring (convincing overqualified people to take a career risk and join your venture), strategic partnerships (persuading large companies to take a chance on the little guy), future financings (key to most venture deals), and ultimate liquidity (getting buy-in from either acquirers or the public on an intrinsic strategic premium).

Presentations are a tool used to excite and inform. Informing is a relatively well understood process in pitch deck creation, but excitement is an absolute rarity. Founders have the unfortunate challenge of dealing with often cynical fund managers who are constantly overwhelmed with the shear volume of opportunities that they see. While founders live and breathe the thrill of building their dream product or solving a central problem to their lives, it is safe to assume that the people you speak with in the venture community (tuned in as they may or may not be) do not have your company's sense of urgency coursing through their veins. And it is likely that your prospective customers, partners, and employees don't either. People of all types require selling.

The great thing about the presentation is that it is a free form document. In many ways, it even subsumes other parts of the evaluation process such as the financial model and the product demo, as each can be expressed either directly or referentially within a linear page turn. But, while PowerPoint has to be one of the most important productivity tools of all time, its standard settings have created a near monotony in tones of discourse and vehicles of persuasion. I would love to see an embrace of a new pitch deck UI.

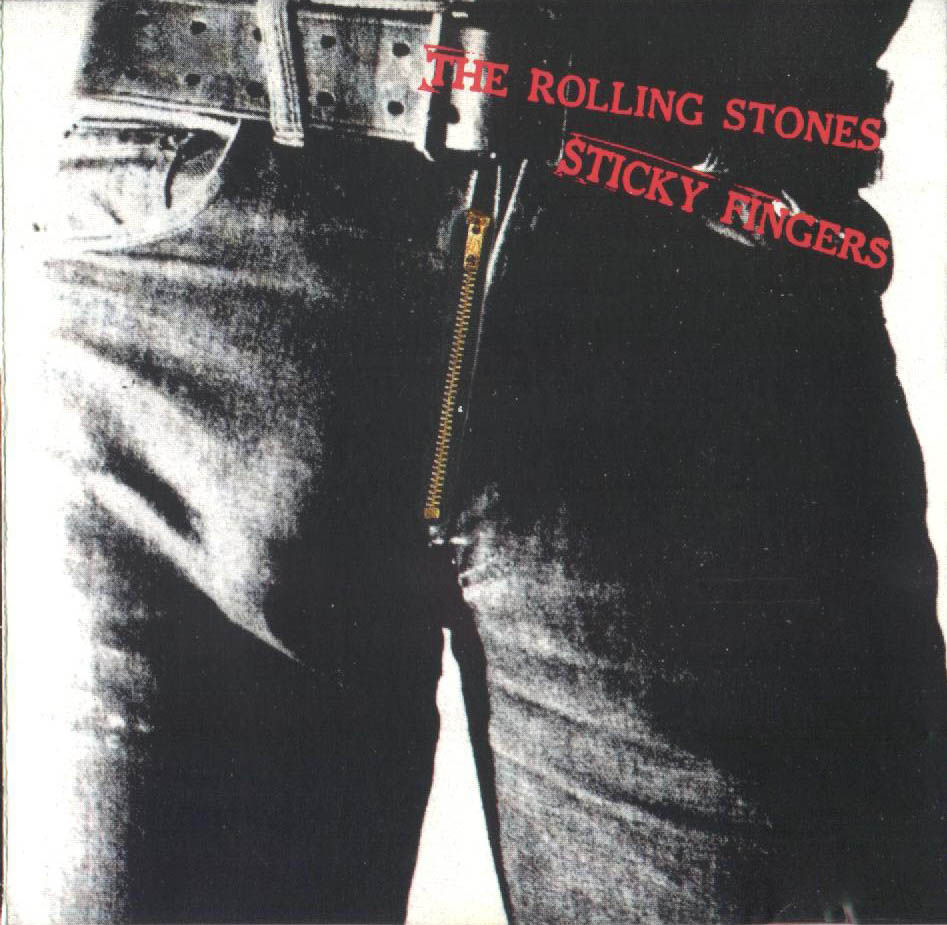

If you are someone that looks at presentations often, you know a good pitch deck UI when you see it. Reading them, your heart can literally skip a beat. One of the original pitch deck UI pioneers of the internet era was a mentor of mine, Josh Koppel. Josh wrote a book in 2000 called Good Grief that changed my life. While an Internet entrepreneur by trade, Josh introduced his format to the world as an autobiography. It reads like an adult picture book: few words on each page. Their interaction with deeply relevant imagery on each page teases the reader between the fascination of looking deeper and the excitement of the page turn. While Josh's book was physical in form, it translated magically into the digital realm. The mouse click became his page turn. The content turned professional. Used to pitch everything from TV pilots to new mobile apps to even his own company when need be, Josh showed me how exciting the story of a product or company can be - even if put together with conventional presentation creation tools (spoiler: Apple Keynote is his layout tool). While I have learned from a number of others, no one has been more impactful in the development of my own style and appreciation for what is possible.

So when you are preparing your next pitch deck, what some of the things you should consider? (1) Every design decision, like in your product, is just that, a choice. Use colors, graphs, fonts, and spacing carefully; (2) considering using imagery - pictures really catch people off guard if editorial instincts are strong, and they very much can be worth 1000 words; (3) consider non-linear formats - such as Prezi, if appropriate - although know that most investors would side with the utility of the print-out over the flash & intrigue of an innovative non-linear narrative experience; (4) challenge yourself to keep it short (Fred Wilson suggests six slides - although I'm comfortable with the looser definition of "leaving your audience wanting more"); (5) make sure that you show it to a few low risk people outside the venture community with little relevant experience to ensure the headline themes are clear; and (6) begin your investor conversations also with low risk audiences - either friends or those that are low on your wish list - for real-time debugging of UI. AB testing works here just as well as in software development.

Happy to field questions or provide examples if folks are interested.